.png)

January 2026 • 6 min read

Across 2025, the impact of generic AI tools became hard to ignore. AI fatigue is now a real phenomenon. Teachers, students, and institutions are more frequently exposed to AI slop, hallucinated answers, and tools that optimize for fluency and compliments, rather than truth. At the same time, there is growing concern around outsourced thinking, reduced engagement, and the erosion of academic trust.

While much of the AI market is racing toward generic scale, a clear lesson from 2025 points in the opposite direction for education. This post shares what school leadership, educators, and students are asking for, and why publishers are emerging as the anchor for safe, effective AI in learning.

Pour yourself a coffee and enjoy the Ludenso insights from 2025.

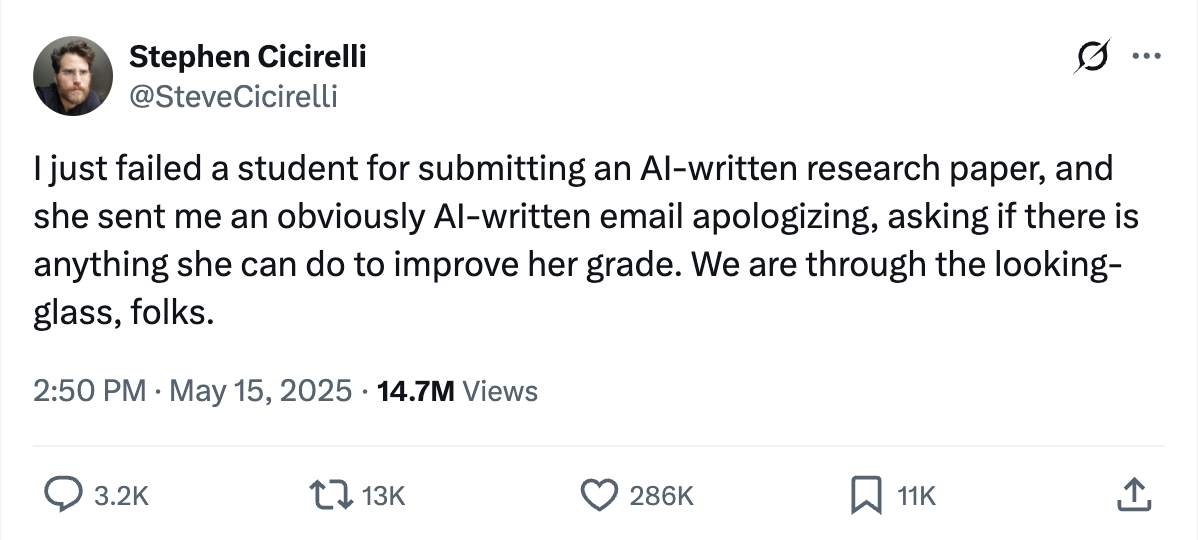

As educators navigate AI on the front line of teaching and assessment, expectations are rising for school and institutional leadership to provide clarity and direction. What many teachers experience as disruption: AI solving assignments and obscuring evidence of learning, quickly escalates into questions of policy, standards, and trust. Below is an example from Stephen Cicirelli, a lecturer at Saint Peter’s University, that went viral when he shared challenges with AI that educators globally can relate to:

Despite this and several other obvious challenges, many educators are engaging with AI in increasingly constructive ways. Educators are actively experimenting with tools such as NotebookLM, ChatGPT, Copilot, and localised AI solutions to save time and develop lesson plans and learning supports that can be adjusted in depth, pacing, and emphasis to meet diverse learner needs.

However, this experimentation exposes a significant structural problem at the institutional level. To get useful, curriculum-aligned support, educators often feel compelled to upload textbook chapters into generic AI tools without clear permission or safeguards. For many, this is not a deliberate choice to bypass IP rules, but a symptom of missing institutional infrastructure and a practical response to the lack of AI support embedded in their learning resources.

Despite these challenges, the productivity gains are tangible, and many leaders now see AI as a valuable part of educators’ professional toolkit.

From a school leadership perspective, the combination of rapid student adoption, informal teacher experimentation, and growing IP and assessment risk has accelerated expectations.

Institutional leaders are now asking:

Publishers are increasingly central to answering those questions.

Educators are pragmatic adopters. In 2025, their expectations of AI became more concrete as classroom use increased and informal experimentation turned into everyday practice.

Across interviews and pilots, educators consistently favored AI tools that:

As AI became a more integrated part of daily teaching, educators also became more aware of the need for stronger AI competence to use these tools well and safely. Questions increasingly shifted from whether AI should be used to how it can best support learning without undermining assessment, pedagogy, or professional responsibility.

This shift reveals an important opportunity for publishers. Beyond delivering trusted teaching resources, publishers are uniquely positioned to help educators develop the skills and understanding needed to use AI responsibly and effectively. This can be achieved by embedding guidance directly into learning materials, through micro courses, or in-person training.

Recent research offers early and important insights into how students use AI, and which approaches support learning versus what undermines it.

A large randomised controlled study by Microsoft Research and the team at the Cambridge University Press & Assessment, with whom Ludenso collaborates closely, compared learning outcomes among 405 students aged 14–15 using three approaches: traditional note-taking, a generic LLM, and a combination of both. Students who took notes, either alone or alongside the LLM, showed significantly better comprehension and long-term retention than those who relied on the LLM alone. Despite this, many students preferred using AI and perceived it as more helpful.

This difference between perceived usefulness and actual learning outcomes points to a potential risk: without traditionally effective learning strategies and tools, like note-taking, and other cognitively active strategies, AI-only use may weaken understanding in the long term. Upcoming PISA results may offer clearer insight into these longer-term effects.

Findings from the USC Center for Generative AI and Society reinforce this picture, showing that most students use tools like ChatGPT for quick answers rather than learning. Encouragingly, the same research shows that when educators actively guide students in how to use AI, students are far more likely to engage with it in learning-oriented ways.

Taken together, these insights point to two clear needs. First, AI should be combined with curated, pedagogical content and learning strategies that keep students actively engaged: supporting reflection and understanding, rather than answer generation. Second, educators need support in learning how to use AI deliberately to strengthen learning.

For publishers, this creates a powerful opportunity to embed AI within structured learning resources that preserve productive friction and help students take a more active role in their own learning.

Across countries and age groups, student needs are strikingly consistent. What stands out is a growing tension between how AI is commonly used (as shown by the research) and what students say they need.

Ludenso’s classroom pilots and student conversations across Europe and the US reveal a nuance to the student demands. When asked directly what they want from an AI assistant, students do not ask for quick help to do the homework for them. They ask for support that helps them learn and understand more:

Taken together, these findings challenge the assumption that students primarily want AI to “do the work for them.” The risk of AI shortcutting learning is real, and it is driven by how tools are designed and the lack of guidance on how to effectively use AI to learn.

The implications are twofold:

From a publishing perspective, this points to a clear opportunity. When AI is embedded directly into textbooks and structured learning resources, students can:

In other words, students benefit most when AI reinforces the textbook, not replaces it. And the publishers who control content structure, pedagogy, and context are uniquely positioned to meet this need at scale.

One pattern repeated across markets: AI solutions built with publishers are the ones teachers have the highest trust in. Editorial quality, pedagogical intent, and strong safety mechanisms are decisive advantages.

What emerged across classrooms was not demand for more AI features, but for safe and trusted AI, grounded in curated content. Publisher-led AI solutions are uniquely positioned to meet those conditions. In a growing sea of AI slop, publishers act as a lighthouse: offering educators and students a fixed point of trusted knowledge to navigate by.